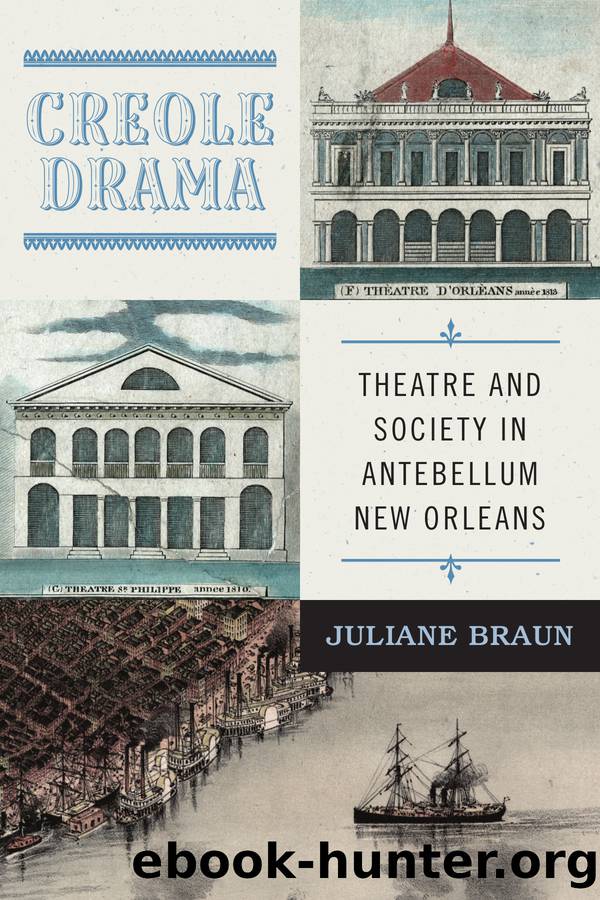

Creole Drama: Theatre and Society in Antebellum New Orleans by Braun Juliane;

Author:Braun, Juliane; [Braun, Juliane]

Language: eng

Format: epub

Tags: LIT004020 Literary Criticism / American / General

Publisher: University of Virginia Press

5

Transatlantic Vistas

Changing Alliances at Home and Abroad

In a poem titled âSong of the Exiled,â New Orleans writer Camille Thierry recalls the ambivalence that surrounded his decision to leave Louisiana for a better life in France. âExile, my friend, I fear, / But must I stay here? . . . No! . . . ,â he writes, explaining that despite the uncertainty he feels about his future on âthe other shore,â nothing keeps him âwhere [he] only feel[s] regrets.â1 Thierry was a successful businessman, a talented writer, and a close associate of some of New Orleansâs most prominent residents. Yet as the son of a liquor merchant from Bordeaux and a New Orleans octoroon, he could never hope to enter the Crescent Cityâs highest social ranks. Instead, like other members of New Orleansâs free black community in the antebellum period, Thierry experienced discrimination, prejudice, and the gradual erosion of his civil rights.

In the first decades of the nineteenth century, Louisiana lawmakers introduced a series of restrictive acts that sought to curtail the overall number of free people of color in Louisiana and attempted to limit their day-to-day activities. Gens de couleur libres were no longer allowed to enter the state, and those who already resided in Louisiana were required to register with their city or parish, indicating their age, sex, color, occupation, place of birth, and the time of their arrival.2 Marriages between free people of color and members of the white or enslaved populations were prohibited, and the publication or distribution of any materials that had âa tendency to produce discontent among the free colored population of this state, or insubordination among the slaves thereinâ was punished with âimprisonment at hard labor for lifeâ or death.3 Those using inflammatory language âin any public discourse, from the bar, the bench, the stage, the pulpit, or in any place whatsoever,â were similarly condemned to long prison sentences or death.4 In 1850 a new law was passed designed to prevent free people of color from congregating in groups larger than six or forming scientific, literary, or charitable associations.5 From 1858 onward, free people of color were no longer allowed to assemble in churches and for funerals unless the gathering was âunder the supervision and control of some recognized white congregation or church.â6 And finally, in 1859 the Louisiana legislature passed an act permitting âFree Persons of African Descent to Select Their Masters and Become Slaves for Life.â7

While the racial climate in antebellum Louisiana deteriorated in the first half of the nineteenth century, people of color in France and in Franceâs overseas possessions experienced gradual improvements. The French Revolution of 1830 brought to power many of the liberals who had been members of the Société de la morale chrétienne (Society of Christian Morality), a benevolent society that had spearheaded Franceâs fledgling antislavery movement in the 1820s. Former société adherents such as King Louis Philippe, his foreign minister Victor de Broglie, and the minister of the navy and the colonies Horace Sébastiani worked to pass a series of laws that liberalized race relations.

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

| Acting & Auditioning | Broadway & Musicals |

| Circus | Direction & Production |

| History & Criticism | Miming |

| Playwriting | Puppets & Puppetry |

| Stage Lighting | Stagecraft |

Call Me by Your Name by André Aciman(19887)

Ready Player One by Cline Ernest(13954)

How to Be a Bawse: A Guide to Conquering Life by Lilly Singh(7150)

Wiseguy by Nicholas Pileggi(5306)

The Kite Runner by Khaled Hosseini(4944)

On Writing A Memoir of the Craft by Stephen King(4654)

Audition by Ryu Murakami(4606)

The Crown by Robert Lacey(4565)

Call me by your name by Andre Aciman(4461)

Gerald's Game by Stephen King(4364)

Harry Potter and the Cursed Child: The Journey by Harry Potter Theatrical Productions(4308)

Dialogue by Robert McKee(4153)

The Perils of Being Moderately Famous by Soha Ali Khan(4060)

Dynamic Alignment Through Imagery by Eric Franklin(3912)

Apollo 8 by Jeffrey Kluger(3504)

How to be Champion: My Autobiography by Sarah Millican(3491)

The Inner Game of Tennis by W. Timothy Gallwey(3463)

Seriously... I'm Kidding by Ellen DeGeneres(3409)

Darker by E L James(3400)